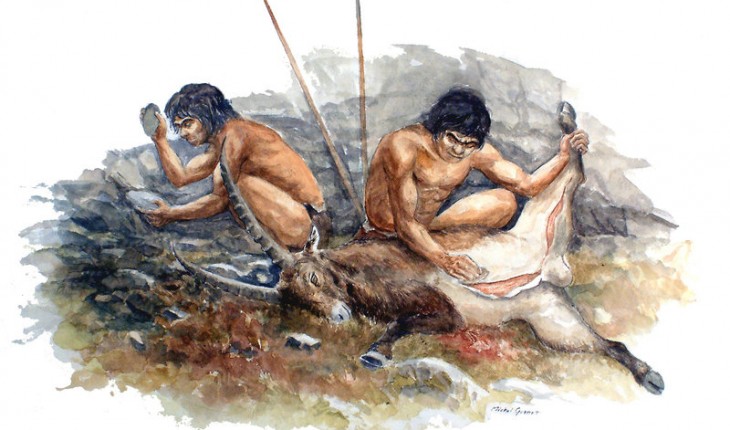

Image: Neanderthal hunters cutting up their kill. Michel Grenet/Science Source

By Maanvi Singh

You know that feeling when your body is really craving a nice salad, but the only thing in your fridge is day-old pepperoni pizza? And you don’t want to go through all the trouble of heading to the grocery store to gather all the ingredients for salad, so you settle for the pizza?

Well, Neanderthals feel you — kind of.

See, researchers are finding that Neanderthals and early humans weren’t all that different — they even got together and made babies every now and then.

But when it came to diet, the two may have had different approaches.

Both were omnivores. But, during the Ice Age, when the climate was constantly fluctuating, Neanderthals tended to chow down on whatever was most readily available, according to a study published this week in PLoS One. During cold spells, Neanderthals — especially those who lived in open, grassland environments — subsisted mostly on meat. During lusher climes, Neanderthals would supplement their diet with plants, seeds and nuts.

Early humans, on the other hand, seemed to stick with a pretty consistent diet regardless of environmental changes: They regularly ate a relatively higher proportion of plant-based foods. Researchers figured this out by studying the tiny, microscopic dings and dents on ancient teeth.

Early humans preparing food — depicted in an engraving from “Grands Hommes et Grands Faits de l’Industrie” circa 1880. CCI Archives/Science Source

“The moment we get our adult teeth, they start to wear down. And the rate at which they wear down is very much related to what you eat — especially if you look at the molars,” explains Sireen El Zaatari, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, who led the study. “This food that you’re chewing is leaving tiny, tiny marks on your teeth.”

Meat — especially cooked meat — is relatively gentle on the chompers, whereas seeds and nuts leave a mark, she says. El Zaatari and her colleagues looked at the teeth of Neanderthals and humans living mainly in Europe throughout the Upper Paleolithic period.

The researchers weren’t able to directly compare a Neanderthal and a human who lived during the exact same time. “Still, we can assume that generally, both groups had access to the same resources,” El Zaatari says. “But what you notice is that Neanderthals and humans ate different ratios of meat and plant-based food.”

What could explain these differences in eating habits? Scientists aren’t really sure. “Maybe it was simply a cultural difference,” El Zaatari says. “Or maybe humans were better at exploiting their environment to acquire food that was harder to get. Unfortunately, we can’t know for sure.”

This research does fit in with other evidence indicating that Neanderthals tended to eat more meat than early humans, says Susan Cachel, an anthropologist at Rutgers University, who wasn’t involved in the study. But examining dental wear isn’t the only way of deciphering our ancestors’ eating habits.

“A better way to look at diet is to look at the chemistry of [tooth] enamel,” Cachel says.

Different plants absorb different amounts of carbon isotopes. Scientists can analyze the ratios of various isotopes on ancient enamel to figure out what sorts of fruits, nuts and vegetation our ancient predecessors ate. So the isotopes in tooth enamel can paint a broad picture of what someone ate throughout their life. On the other hand, “the advantage of looking at [dental wear] is that you get a fuller picture of what all they were eating right up to the time when they died,” says Shara Bailey, an anthropologist at New York University.

Bailey, who wasn’t involved in the recent study, either, says this new research adds to our growing understanding of early human life.

Perhaps humans outlived (and to some extent — genetically swallowed up) the Neanderthals because they were better at making their environment work for them, Bailey says. “At this point, we can only speculate. This is one more bit of information we can use.”