By Farzin Espahani

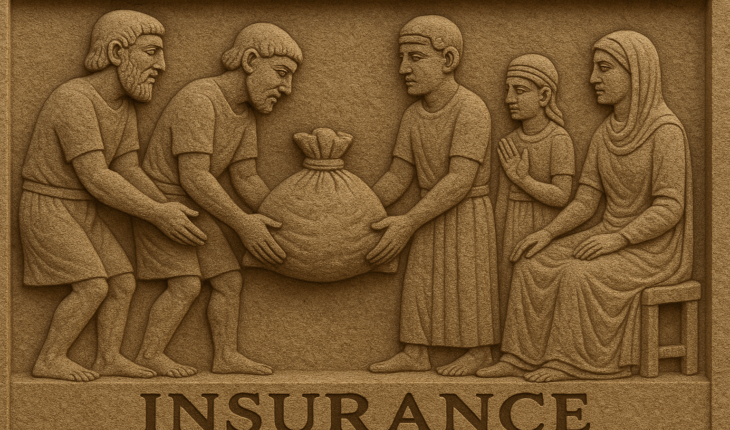

In the modern world, insurance is often associated with paperwork, premiums, and large corporations. But long before the rise of modern financial systems, the concept of insurance existed in a very different form. At its core, insurance is about managing uncertainty and sharing risk. And when we look at the long history of human societies, we find that people have always found ways to protect themselves and each other from unexpected loss.

To understand where insurance came from, we need to begin with the roots of human cooperation. Homo sapiens evolved as social beings. Our survival often depended not on individual strength, but on our ability to work together, to share resources, and to care for one another during times of need. Early human groups, especially hunter-gatherers, practiced food sharing and mutual support as a way to ensure survival. When one person failed to find food, another might succeed. Over time, these exchanges built trust and created a kind of informal safety net.

Among foraging groups, this sharing was not just generosity. It was a strategy. It helped reduce the risk of starvation and made life more predictable. Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins called this system “generalized reciprocity,” where people help each other without keeping strict accounts. This laid the foundation for what we might now call social insurance (Sahlins, 1972).

Kinship played a major role in these early forms of protection. People looked after their relatives because doing so increased the chances that their genes would survive. But human beings also formed social bonds beyond blood ties. Through rituals, shared beliefs, and group membership, they created what anthropologists call “fictive kinship.” These bonds extended obligations and support across larger groups (Service, 1962).

Ceremonial gift-giving, communal feasts, and even marriage exchanges served multiple purposes. One important function was to create alliances that could be counted on in times of need. When disaster struck, the wider network stepped in. These traditions became the early cultural expressions of risk-sharing (Mauss, 1925).

Archaeology gives us some of the earliest physical evidence of organized risk management. In the Neolithic period, many societies built communal storage systems for grain. Sites like Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey contain evidence of large storage rooms. These granaries helped people survive bad harvests. They were not just about saving food. They represented a shared commitment to support the group in times of scarcity (Hodder, 2006).

Burial practices also reveal early insurance-like behavior. In ancient societies, funerals were often elaborate events, requiring significant resources. Many times, these costs were covered by extended kin or by the community. This ensured that the dead were honored properly and that their families were not left impoverished. In ancient Egypt, burial societies collected contributions from members to fund proper funerals. These societies functioned very much like modern burial insurance plans (Davies, 2001).

As societies became more complex, so did their methods of managing risk. In Mesopotamia, as early as 2000 BCE, merchants practiced a form of maritime insurance. Under the Code of Hammurabi, traders could take out loans that were forgiven if their shipments were lost at sea. This arrangement transferred the risk of loss from the merchant to the lender, laying the groundwork for modern marine insurance (Bottero, 1992).

In ancient Greece and Rome, similar systems emerged. In Rome, funeral clubs known as collegia pooled member contributions to ensure proper burial rites. These clubs operated under clear rules and represented early examples of mutual aid societies (Rawson, 1986).

In the Islamic world, risk-sharing took on a religious form. Conventional insurance was often seen as involving uncertainty or interest, which were not allowed under Islamic law. Instead, Muslim communities developed the concept of takaful, a cooperative insurance model based on mutual assistance. Members contributed to a pool, and those who suffered a loss received compensation. Takaful remains a widely used model in many Muslim-majority countries today (Khan, 2007).

During the Middle Ages, as Europe transitioned from the Roman world to a feudal one, guilds and religious groups took on the role of insurers. Merchant and craft guilds provided their members with protection against loss of tools, fire, or theft. They also supported members during illness or after death. These guilds collected dues and created communal funds to manage risk. They were early institutions that combined economic function with social solidarity (Epstein, 1991).

In parallel, religious fraternities and village communities also pooled resources to help their members. Whether helping a widow, rebuilding a burned house, or supporting a sick member, these networks formed the backbone of social security in pre-modern Europe (Bloch, 1961).

In Britain, the Great Fire of London in 1666 changed the course of insurance history. It destroyed over thirteen thousand homes and highlighted the need for organized protection. Shortly after, fire insurance companies emerged. They offered coverage to property owners, collecting regular payments and providing compensation after a fire. Fire marks appeared on buildings, identifying which insurer covered the structure. This was one of the first examples of modern risk assessment (Pearson, 2004).

At the same time, London was becoming a global trade hub. At a coffee house owned by Edward Lloyd, shipowners and investors met to share the risks of overseas voyages. This practice evolved into Lloyd’s of London, a marketplace for underwriting. Investors would each cover a portion of a ship’s value, spreading the potential loss. This system allowed for greater risk-taking and expansion of trade (Kingston, 2007).

Insurance, in its various forms, is more than a financial tool. It is a reflection of cultural values and social structure. Different societies organize risk-sharing in different ways. In individualistic cultures, insurance tends to be commercial and contractual. In more collectivist cultures, mutual aid and state-funded systems are more common (Hofstede, 2001).

For example, in the Scandinavian countries, public insurance plays a major role in health care and unemployment protection. These systems are funded through taxation and reflect a strong belief in social solidarity. In contrast, the United States has a more privatized insurance model, where many people purchase individual plans and companies compete for customers (Esping-Andersen, 1990).

One challenge that insurance always faces is the risk of moral hazard. This occurs when people take greater risks because they know they are protected. Different cultures and systems address this in different ways, through either strict regulation or community oversight (Arrow, 1963).

Interestingly, some of the newest insurance models are looking back to the old ones for inspiration. Peer-to-peer insurance platforms now allow groups of people to pool their resources and share unused funds. These digital mutual aid societies echo the burial clubs of Rome or the guild funds of medieval Europe.

Wearable technology and behavioral data are also changing the way insurers evaluate risk. Today, an insurance company can track your driving habits, exercise routine, or sleep patterns. This personalization mirrors older systems where people were rewarded or punished based on their behavior and reputation in the community.

From food sharing among hunter-gatherers to AI-driven insurance pricing, the concept of risk-sharing has remained a central part of human life. It has evolved in form but not in function. It still serves the same basic purpose: to protect individuals by linking their fate with that of others.

Insurance is not just a financial instrument. It is a human invention rooted in cooperation, trust, and the shared experience of uncertainty. It is both ancient and modern, practical and symbolic. Understanding its origins helps us see that it is not a product of bureaucracy but a reflection of our deepest social instincts.

References:

Arrow, K. J. (1963). Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care. American Economic Review, 53(5), 941–973.

Bloch, M. (1961). Feudal Society. University of Chicago Press.

Bottero, J. (1992). Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. University of Chicago Press.

Davies, W. V. (2001). Egyptian Hieroglyphs. British Museum Press.

Epstein, S. R. (1991). Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. University of North Carolina Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Hodder, I. (2006). Çatalhöyük: The Leopard’s Tale. Thames & Hudson.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Sage.

Khan, M. F. (2007). Islamic Insurance: Theory and Practice. Islamic Research and Training Institute.

Kingston, C. (2007). Marine Insurance in Britain and America, 1720–1844: A Comparative Institutional Analysis. Journal of Economic History, 67(2), 379–409.

Mauss, M. (1925). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. Cohen & West.

Pearson, R. (2004). Insuring the Industrial Revolution: Fire Insurance in Great Britain, 1700–1850. Ashgate.

Rawson, B. (1986). The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives. Cornell University Press.

Sahlins, M. (1972). Stone Age Economics. Aldine de Gruyter.

Service, E. R. (1962). Primitive Social Organization: An Evolutionary Perspective. Random House.