This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

By: Professor of Palaeoclimatology, UCL

Human society rewards individuals who can handle complex social interactions and control large groups of people. Extreme examples of this power are comedians who can fill stadiums entertaining 70,000 people, or politicians who, through their rhetoric and charm, convince millions of us to vote for them so they can run our lives. Intelligence, humour, and charisma are used to co-opt a greater share of resources for themselves and their family. In fact, many scientists now think this is exactly why we evolved a very large brain.

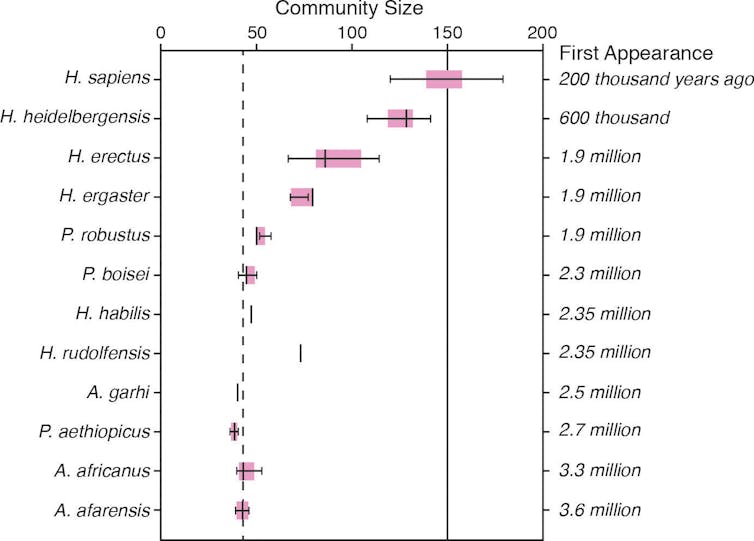

Originally, large brains were thought to be essential for the making of stone tools, and this is why Homo habilis (skillful man) was thought to be the start of our Homo genus some 2.5m years ago. But we now know that many other animals make and use tools. We also know hominins living 3.3m years ago were already using stone tools half a million years before Homo evolved.

So why did we evolve a large brain if it wasn’t essential for tool making? One reason is that existing in a large social group is very mentally taxing. Those who are better at playing the social game will have more access to mates and resources and will be more likely to reproduce. As the groups get larger, so the computational power needed to keep up with the interconnections grows exponentially, as does the stress.

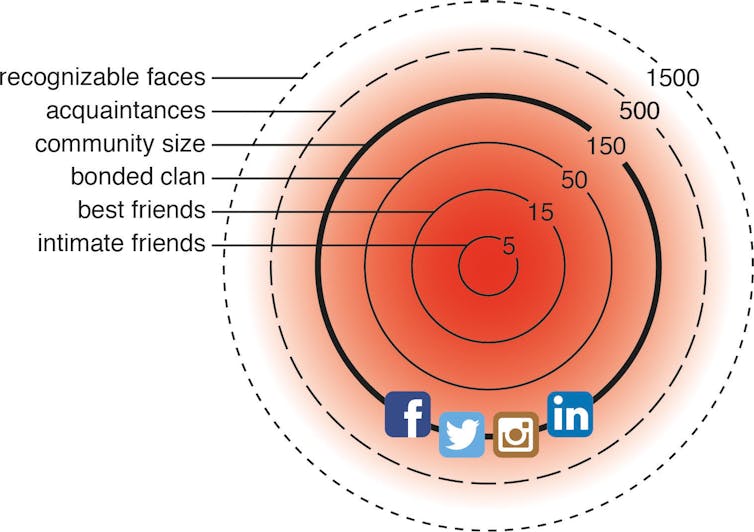

Modern humans like to live and interact in communities of about 150 people. This magic number is found in the population of stone age settlements, villages in the Domesday Book (a census of England in 1085 AD), 18th-century English villages, modern hunter-gatherer societies, Christmas card distribution lists, and even modern Twitter communities – just to name a few examples.

Groups of 150 are about what we would expect, when comparing the size of human brains to those of our relatives. Community size in primates is linked to the size of the neocortex region of the brain, where all social cognitive processing occurs. Other primates, with smaller brains, live in smaller groups. Species, such as the baboon-like mandrill of Central Africa, that do gather in larger numbers only contain females and children in their “horde” so these are not true mixed sex social groups. If one extrapolates the relation between brain and group size in other primates then humans with their very large neocortex extend the graph to a community size of 150.

This relationship is extremely useful as it means we have a way of estimating group size in our extinct ancestors. Those a few million years ago, lived in groups of 50 or so. The big change occurs with Homo erectus at about 2m years ago when groups jumped up to nearly 100; then Homo heidelbergensis at 130 and, of course, modern Homo sapiens at 150.

Human ancestors with larger brains would have been better at hunting and gathering food, better at sharing the spoils, and better at fighting off predators.

Yet there are also significant survival risks associated with a larger brain such as an increased need for food. Mother mortality rates also increase due to what is known as the “obstetric dilemma”, which refers to the danger of giving birth to a baby with such a large head. While chimpanzees give birth relatively easily as their heads are significantly smaller than the birth canal, human heads are much larger, and so the baby has to twist twice to get through the hips.

For the selection pressure to continue – for brains to keep getting larger – there must have been huge rewards for being smart and having a bigger head. One of those rewards was better social skills. The increased complication of childbirth would require mothers to have help from others, and individual females who were more socially adept would get more help, therefore they and their infants were more likely to survive. This positive feedback loop drove the evolution of larger brains as a means of having greater social influence.

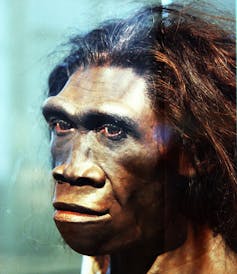

Underlying this social brain hypothesis is an internal arms race to develop the higher cognitive skills to enable greater social control. Clearly, with the emergence of Homo erectus, H. heidelbergensis, and eventually H. sapiens, the positives outweighed the negatives. In my latest book, Cradle of Humanity, I discuss how this was driven by rapid environmental changes in East Africa, increased competition for resources within the species as the population expanded, and competition with other species.

A modern reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus. Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA

We humans emerged from Africa with an extremely large, flexible and complex “social brain”. This has allowed us to live relatively peaceful lives around millions of others. This does not, however, mean that we live in harmony with each other, instead we have swapped physical conflict for social competition. We are constantly strengthening our alliances with friends and partners while working out how to keep up and if possible surpass our peers in terms of social position. And that is why it is so stressful simply being human.