There is a place in the world where all the forces of nature merge and create an environment so unique that there are animals like nowhere else on Earth. Rainforest-covered volcanoes soar out of an ocean filled with vibrant coral reefs, ecosystems meeting to create unrivalled biodiversity.

This is the land where Alfred Russel Wallace spent 8 years exploring from 1854 to 1862, and where he made some of the most important scientific discoveries of all time. Wallace played a key role in the discovery of evolution, and also laid the foundations for our understanding of how islands influence the natural world.

To Wallace, this region was known as the Malay Archipelago. To modern biologists, it is Wallacea: thousands of South-East-Asian islands that lie between Asia and Australia. Everything here shouts out the magnificence of life.

Wallace’s research tried to answer one of the most profound questions of all: where does life come from? His exploits would change the course of history.

Born in 1823 in Wales, Wallace was a man of modest means, but he had a passion for nature and he chose to follow it. He started out collecting insects as a hobby, but eventually his yearning for adventure led him to explore the world.

Luckily for Wallace, Victorian Britain was discovering an interest in weird and wonderful insects, so the demand from museums and private collections for these beasts was growing. Wallace was able to make a living doing what he loved: collecting beetles and other insects.

But his first trip ended in disaster.

Wallace ventured to the Amazon in South America. Its giant forests promised a wealth of new species, sure to put him on the scientific map. At first he travelled with friend and fellow naturalist Henry Walter Bates, but they eventually split up to cover more ground, roaming the unexplored tributaries of the Amazon.

The trip took 6 weeks and involved every mode of transport in existence at the time

After four years Wallace set off for home, but his boat caught fire in the middle of the Atlantic. Everyone survived, but Wallace had to watch in despair as his specimens went up in flames – including live animals he was bringing home that were trying to jump free of the flames.

This must have been a harrowing experience: Wallace had to watch four years of work, and his entire living, go up in flames. But he did not let it stop him.

In 1854, aged 31, Wallace set off on another adventure, this time to the Malay Archipelago. This part of the world was so far from Wallace’s home, many Europeans at the time did not even know it existed.

The adventure started with a journey from London to Singapore. In stark contrast to modern air travel, the trip took 6 weeks and involved every mode of transport in existence at the time. Wallace even marvelled at how quick it was.

His luggage would make even the heaviest packer look like they were travelling light. Victorians took everything with them, from furniture and clothes to salt and pepper. But as well as these “essentials”, Wallace needed all his scientific equipment for collecting specimens, including nets, boxes, pins and cages.

I think how many besides myself have longed to reach these almost fairy realms

He made his base in Singapore, and from there he spent eight years travelling to different groups of islands in the region.

In a letter to his mother in 1854 he describes a typical day: “Get up at half past five. Bath and Coffee. Sit down and put away my insects of the day before, and set them safe out to dry. Charles [his assistant] mending nets, filling pincushions, and getting ready for the day. Breakfast at eight. Out to the jungle at nine. We have to walk up a steep hill to get to it, and always arrive dripping with perspiration. Then we wander about till two or three, generally returning with about 50 or 60 beetles, some very rare and beautiful. Bathe, change clothes, and sit down to kill and pin insects. Charles ditto with flies, bugs and wasps; I do not trust him yet with beetles. Dinner at four. Then to work again till six. Coffee. Read. If very numerous, work at insects till eight or nine. Then to bed.”

Wallace found himself humbled by the new and exciting things he saw. He later recalled: “As I lie listening to these interesting sounds, I realise my position as the first European who has ever lived for months together in the Aru islands, a place which I had hoped rather than ever expected to visit. I think how many besides myself have longed to reach these almost fairy realms, and to see with their own eyes the many wonderful and beautiful things which I am daily encountering.”

His eight years of observation led him to some startling conclusions.

At this time, scientists had begun to realise that the Earth, and the life on it, was far older than previously thought. Instead of just a few thousand years old, the world was millions of years old.

The idea is like truth itself, so simple and obvious that those who read and understand it will be struck by its simplicity

A key thinker in this area was the geologist Charles Lyell. He argued that the Earth had changed over time, shaped by long slow processes such as the building of mountains.

Wallace had been an avid reader on this topic. Being a free-thinking, spirited person, he was not afraid of telling people what he had found and adopting controversial ideas, so he happily promoted Lyell’s ideas. But he also took the argument a step further and suggested that life also changed over time. A species like an orangutan, Wallace argued, is not fixed, but can gradually transform from generation to generation.

In 1858, Wallace was on the island of Ternate in Indonesia. There he wrote what became known as the “Ternate essay“: a piece of writing that was to change our understanding of life forever.

In his essay, Wallace argued that a species would only turn into another species if it was struggling for existence.

In the immediate aftermath, they both became famous

Wallace’s friend Bates was one of many scientists delighted by the idea of evolution by natural selection. In a letter to Wallace, he wrote: “The idea is like truth itself, so simple and obvious that those who read and understand it will be struck by its simplicity; and yet it is perfectly original.”

Wallace sent his ideas to the English naturalist Charles Darwin, with whom he often exchanged letters. As it happened, Darwin had been working for 20 years on his own theory of natural selection, partly inspired by his 1835 visit to the Galápagos Islands.

Darwin had not published his ideas, because he was afraid of a backlash. He quickly realised that Wallace’s discoveries matched up with his own, and resolved to take the plunge. He decided to present both their papers at the same time, so that both men would get credit for having independently discovered evolution.

In the immediate aftermath, they both became famous. But after Darwin published his book On the origin of species by means of natural selection in 1859, he became known as the man who discovered evolution. Most people forgot about Wallace.

Among scientists, Wallace is better known for his discovery of “island biogeography”: the ways island living shapes the mix of species. He noticed big differences between animals occupying nearby islands, most notably between Bali and Lombok. “The great contrast between the two divisions of the archipelago is nowhere so abruptly exhibited as on passing from the island of Bali to that of Lombok,” he later wrote.

Unusually deep water separated the two islands, and Wallace realised that this meant most species could not pass between them.

Wallace had collected over 125,000 species, 5,000 of them new to science

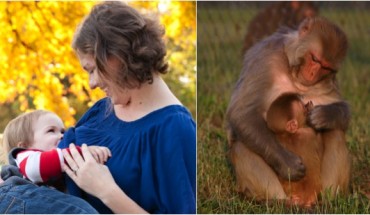

The Bornean and Sumatran orang-utans are another example. They are similar but separate species that only exist on their namesake islands.

Wallace also realised that most of the islands were once connected to either the Australian or Asian mainland. When sea levels rose, they became cut off, and the species living on them were stranded. That meant parts of South East Asia had Asian fauna while the rest had Australian.

The dividing line between Asian and Australian fauna is known as the Wallace line.

He also wrote extensively about colour, asking why animals have evolved so many different colours. A study published in October 2016 reviewed Wallace’s ideas in the light of modern research, and found that, despite working from a much smaller knowledge base than we have today, he “missed little”.

If you do not succumb to foot rot, you will be eaten alive by all the biting creatures you can think of

Wallace had collected over 125,000 species, 5,000 of them new to science. They still sit in museums all over the world today.

His book on the expedition, The Malay Archipelago, was the most significant documentation of that region at the time and even today it is still read by many scientists, travellers and adventurers. It was published in 1869 and has never been out of print.

Following in Wallace’s footsteps, I visited South East Asia’s jungle-covered islands in June and July 2016.

This jungle paradise is often disturbed by an eerie sound: chainsaws reverberating through the trees

You sweat so much that clothes get drenched in an instant and are impossible to dry again. This may sound horrendous, but it is worth it to be amongst the flora and fauna of such a lush and functioning ecosystem.

Dawn is broken by a chorus of birds, the noise rippling out across the canopy like the opening movement of a symphony.

As the light and heat of the day takes over, cicadas dominate the soundscape. They drown out almost everything else, save the bark of a hornbill and the beating of its wings as it flies off, or the rattle of leaves as monkeys swing through the trees overhead.

Wallace cautioned that “modern civilisation is now spreading over the land”

Rivers run over soft limestone lips, forming spectacular layered cascades. These were once built up layer by layer, but now time and water are breaking them down.

But today this jungle paradise is often disturbed by an eerie sound: chainsaws reverberating through the trees. Even though the region is a biodiversity hotspot, habitat destruction is putting many species at risk.

Wallace foresaw the problem over 100 years ago.

Wallace was particularly enthusiastic about the island of Java, which he described as “probably the very finest and most interesting tropical island in the world”, complete with “beautiful and varied” wildlife of “peculiar forms found nowhere else upon the globe”. To him, it was a place where tigers and rhinoceroses still roamed undisturbed.

The world was not created for the benefit of humanity

But he cautioned that “modern civilisation is now spreading over the land”. That trend has only continued.

Today Java is the most populated island in the region, inhabited by 145 million people. Forests are still being cut down, the Javan tiger is extinct and the Javan rhinoceros is the most threatened rhino species in the world.

Wallace warned his readers that the world was not created for the benefit of humanity. “Trees and fruits, no less the varied productions of the animal kingdom, do not appear to be organised with exclusive reference to the use and convenience of man,” he wrote in The Malay Archipelago.

Given how much else Wallace was right about, perhaps we should all take this message to heart.